Portrait

Analog Studio

Prof. Mark Raymond

, Soumya Dasgupta

Jan, 2021

Analog Studio

Prof. Mark Raymond

, Soumya Dasgupta

Jan, 2021

As part of the Analog Studio series of work, students created a series of drawings to enhance our awareness of spatiality, architectural sensibility, and personal history. The six drawings included a one word title prompt, sequentially portrait, assembly, personal room, common room, urban, and landscape.

As the project brief of the figure was introduced and I started to observe my face more, I became interested in capturing the temporal element on my face - hair. Although one could make the argument that one’s perception of oneself is always in flux, especially if the self-portrait is carried out in a live drawing, I am drawn to the constant state of change hair is always in. This fascination partly stems from the fact that I have never grown my hair out before. My shoulder-length hair is the result of the covid-19 pandemic and visually documents the duration of the ongoing pandemic.

Cotemplating deeper on my fixation on hair as a subject, I came to realise that my long hair is a celebration of liberty and individuality. If I had not been away from home (Taiwan), I would have happily obliged a family member’s prompt for a haircut. It was only because the US was affected much worse than Taiwan by the pandemic that all businesses shut down, making it impossible for me to get a haircut at first and gave me this opportunity of growing my hair out. It is with the excuse of not being able to get a haircut did I get this chance of rightfully challenging gender appearance norms.

My long hair is also a different way to connect to my family and culture. In ancient Chinese culture, long hair is the norm, as one’s body is considered to be a gift from one’s parents and discarding parts of it – hair included - was thought to be an ungrateful act towards your parents. My long hair also gave me a new connection with my mother, who taught me how to brush and care for my hair over the webcam, an activity and connection I never had with my mother before.

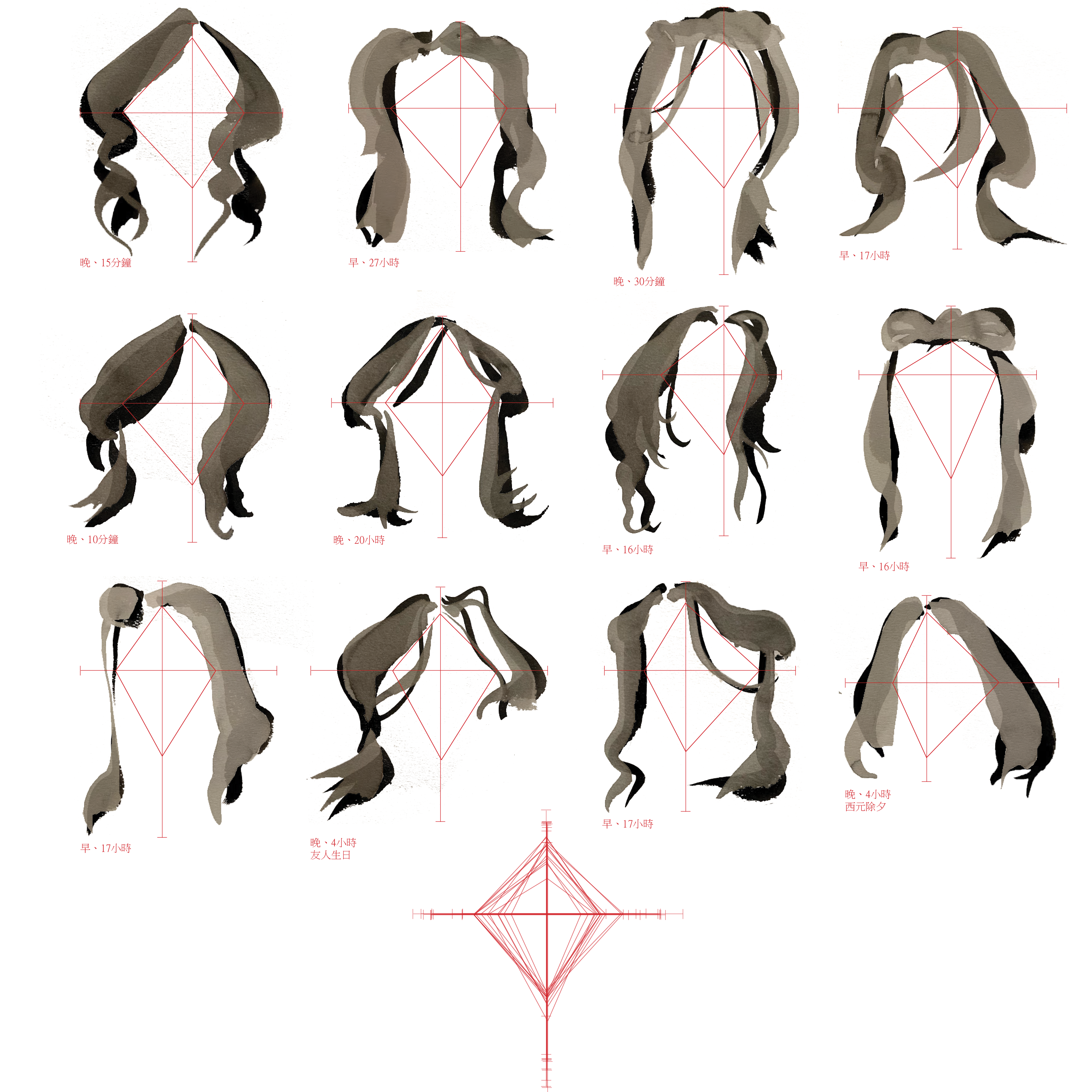

In my self-portrait, I treat my hair as an independent organism – a choice I made early on. This is because I have come to realise that long hair behaves very differently from short hair and is often untamed. I decided I would depict my hair “styles” with multiple attempts, with a constant of using calligraphy brushes and ink. The choice of medium is both cultural and familial, as I practised calligraphy when I was very young but stopped because I felt unconfident when compared to my mother, who is a very skilled Chinese calligrapher in the Yen style.

Each depiction is drawn by a calligraphy brush and ink, although the ink deviates from traditional calligraphic practices because is it washed down, the style of drawing keeps traditional calligraphic conventions – When writing Chinese calligraphy, each stroke is single and final, so no space-filling or edge-fixing is allowed. The depictions follow this calligraphic rule. Finally, red geometric lines are annotated over the overlaid depictions, as an attempt to explore patterns that might emerge out of the various hairstyles. These annotations mark out the total width and height of the hair volume, while the diamond marks out the parameters of the face. Each hairstyle is also coupled with textual data, indicating the time of day, and time since the hair was washed, transforming this personal and artistic exercise into a scientific analysis.

As the project brief of the figure was introduced and I started to observe my face more, I became interested in capturing the temporal element on my face - hair. Although one could make the argument that one’s perception of oneself is always in flux, especially if the self-portrait is carried out in a live drawing, I am drawn to the constant state of change hair is always in. This fascination partly stems from the fact that I have never grown my hair out before. My shoulder-length hair is the result of the covid-19 pandemic and visually documents the duration of the ongoing pandemic.

Cotemplating deeper on my fixation on hair as a subject, I came to realise that my long hair is a celebration of liberty and individuality. If I had not been away from home (Taiwan), I would have happily obliged a family member’s prompt for a haircut. It was only because the US was affected much worse than Taiwan by the pandemic that all businesses shut down, making it impossible for me to get a haircut at first and gave me this opportunity of growing my hair out. It is with the excuse of not being able to get a haircut did I get this chance of rightfully challenging gender appearance norms.

My long hair is also a different way to connect to my family and culture. In ancient Chinese culture, long hair is the norm, as one’s body is considered to be a gift from one’s parents and discarding parts of it – hair included - was thought to be an ungrateful act towards your parents. My long hair also gave me a new connection with my mother, who taught me how to brush and care for my hair over the webcam, an activity and connection I never had with my mother before.

In my self-portrait, I treat my hair as an independent organism – a choice I made early on. This is because I have come to realise that long hair behaves very differently from short hair and is often untamed. I decided I would depict my hair “styles” with multiple attempts, with a constant of using calligraphy brushes and ink. The choice of medium is both cultural and familial, as I practised calligraphy when I was very young but stopped because I felt unconfident when compared to my mother, who is a very skilled Chinese calligrapher in the Yen style.

Each depiction is drawn by a calligraphy brush and ink, although the ink deviates from traditional calligraphic practices because is it washed down, the style of drawing keeps traditional calligraphic conventions – When writing Chinese calligraphy, each stroke is single and final, so no space-filling or edge-fixing is allowed. The depictions follow this calligraphic rule. Finally, red geometric lines are annotated over the overlaid depictions, as an attempt to explore patterns that might emerge out of the various hairstyles. These annotations mark out the total width and height of the hair volume, while the diamond marks out the parameters of the face. Each hairstyle is also coupled with textual data, indicating the time of day, and time since the hair was washed, transforming this personal and artistic exercise into a scientific analysis.